From Allopath to Homeopath - An insight into the medical practice of a "regular" who converts to a"quack". (Part 2)

Hidden Knowledge Part 2 - Testimonial continued, including some stats of Allopathy vs Homeopathy

This post is the continuation from Part 1, if you haven’t read it yet start - HERE

“How I Became a Homoeopath”

A testimonial by William H. Holcombe of New Orleans (1869)

Continued from page 16 - HERE

This palpable failure of Allopathy (call it “regular, rational, scientific medicine,” if you choose) in a disease in which the symptoms are so striking and the indications of treatment so plain, set me to thinking, and I began to ask myself if we had not over-estimated its real value and importance in all other diseases. I gradually passed into a skeptical phase of mind. I became quite disgusted with the practice of my profession. I began to think with Bichat and Rostan, that the Materia Medica was a strange medley of inexact ideas, puerile observations, and illusory methods. I admired the remark of the dying Dumoulin, that he left the two greatest physicians behind him—diet and water; and I echoed in my private cogitations the exclamation of Frappart: “Medicine, poor science!—doctors, poor philosophers ! —patients, poor victims!”

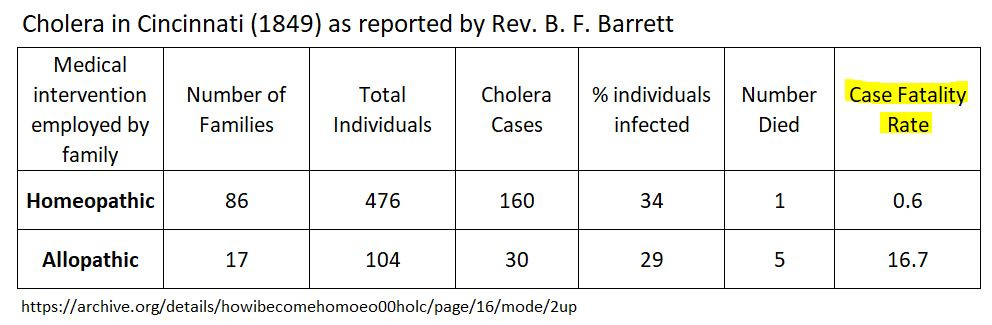

I was roused from this state of disgust, incredulity and apathy in the fall of 1849, by floating rumors of the successful treatment of cholera, at Cincinnati, by Homoeopathy. First one friend, and then another, echoed these marvelous stories, professing to believe them. A letter from Rev. B. F. Barrett, of Cincinnati, was published in the papers, well calculated to excite attention and inquiry. Mr. Barrett (afterwards a very kind friend) was personally known to me as a gentleman of distinguished worth and intelligence, and of unquestionable integrity. I knew perfectly well that if human testimony is worth anything at all, Mr. Barrett’s testimony was to be believed.

Mr. Barrett’s statement was in substance this: he had one hundred and four [104] families under his pastoral charge. Of these, eighty-six [86] families, numbering four hundred and seventy-six [476] individuals, used and exclusively relied upon the Homoeopathic treatment; seventeen families [17], numbering one hundred and four [104] individuals, employed the old system. Amongst the former there were one hundred and sixty [160] cases of cholera and one death; amongst the latter thirty [30] cases and five deaths. This amazing difference between the two methods was supported by the assertion, that twenty cases of cholera occurred in the iron foundry of Mr. James Root, a respectable member of his congregation, all of which were Homoeopathically treated, without a single death.

Here is this data in table form:

In the archives I have come across a lot of statistical data that looks just like this. I find this shocking. We are jabbed today because of Allopathic medicine’s ignorance and failure to treat disease, so they have resorted to “preventative” measures that don’t actual prevent infection! But I digress.

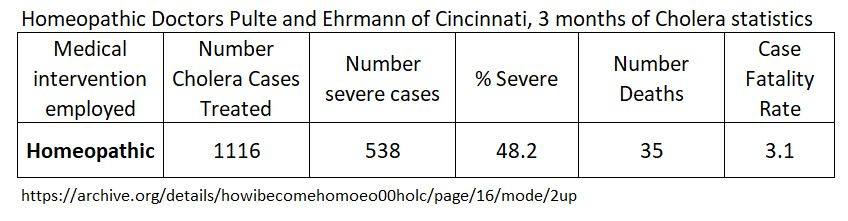

About the same time Doctors Pulte and Ehrmann, of Cincinnati, published statistics of their treatment for three months. They managed eleven hundred and sixteen [1116] cases of cholera, of which five hundred and thirty-eight [538] cases were of the severe type; from sixty to seventy [60-70] collapsed, with thirty-five [35] deaths. They gave the names, dates and addresses of all their patients, so that the facts could be verified, and challenged investigation and comparison.

I present this data here in table form:

Of course I knew that clergymen and aristocratic ladies had a very great penchant for Homoeopathy, and other new things, and that all the quacks and impostors in the world, as well as the “regulars,” appeal to statistics to support their pretensions. Still, making all due allowance for the extravagance of enthusiasm, credulity, imagination and predilection, and also for errors in diagnosis and inaccuracies of detail, there was enough residuum of solid truth in all this to bring me silently to the conclusion — “ There’s something in Homoeopathy, and it deserves investigation.”

When I made up my mind to give Homoeopathy a fair trial, I did it in the right manner. I did not read Professor Simpson’s big book against it, nor Professor Hooker’s little book against it, nor yet Professor Holmes’ funny prose and poetry against it, and then tell my friends that I had studied Homoeopathy, and found nothing in it;— that is one very common Allopathic way of studying Homoeopathy from the Allopathic standpoint.

Nor did I get Hahnemann’s works, and read them with my old pathological spectacles, and decide that the why and the how and the wherefore of infinitesimals were all incomprehensible, and that Homoeopathy was a delusion;—that’s another Allopathic way of studying Homoeopathy, almost as absurd as the first.

No, I believed with Hugh Miller, that scientific questions can only be determined experimentally, never by a priori cogitations. I got a little pocket cholera case, containing six little vials of pellets and a printed chart of directions. I determined to forget all that I knew for the time being, and to obey orders under the new regime, with the unquestioning docility of a little child. I awaited my next patient like a hunter watching for a duck.

I was called up in the middle of the night, to see a poor fellow said to be dying of cholera on a flatboat which had just landed. I found him collapsed; he was cold and blue, with frequent rice-water discharges, and horribly cramped. His voice was husky, pulse feeble and fluttering; he was tossing about continually, begging his comrades to rub his limbs.

I immediately wrote a prescription for pills of calomel, morphine and capsicum, and dispatched a messenger to a drug store. This was to be my reserve corps—ready for use if the infinitesimals failed. I consulted the printed direction: they ordered cuprum when the cramps seemed to be the prominent symptom. I dissolved some pellets in a tumbler of water, and gave a teaspoonful every five minutes. I administered the simple remedy, apparently nothing, with incredulity and some trepidation. “I have no right,” said I to myself, “to trifle with this man’s life. If he is not better when the pills come, I will give them as rapidly as possible.”

Oh! for a strong word at that moment from James John Garth Wilkinson, of London, or a page of his luminous writings, which coruscates athwart the darkness of his age like the fire of heaven—Wilkinson, whose renown is such that Emerson declares him to be the greatest man he saw in Europe ! — (mark you, a Homoeopathic doctor!) — “the Bacon of the nineteenth century,” whose mind has “a very Atlantic roll of thought!” How I could have been encouraged and strengthened by such a paragraph as this from his “War, Cholera, and the Ministry of Health.”

“The dimensions of power are not weighed by scales, or told off on graduated bottles, but reckoned by deeds done. When I am called to an inflammation, I know that aconite and belladonna in billionths of a drop are a vast healing power, because I have cured, and daily do cure, formidable inflammations in their outset by these means. I look upon my little bottles as giants — as words that shake great diseases to their marrows, and into their ashes, and rid the whole man of a foe life-size. Away, then, with the bigness based on quantity, and which sits like a vulgar bully in the medical shops. Great cures determine the only greatness which sick men or their guardians can recognize in medicine.”

The messenger had gone for the pills a good way up town. He had been obliged to ring a long while before he could rouse the sleeping apothecary, and it was quite three-quarters of an hour before he rushed on the boat with the precious Allopathic parcel.

My patient had become quiet; his cramps had disappeared, and he was thanking me in his hoarse whisper for having relieved him of such atrocious pains. The Allopathic parcel was laid on the shelf. I consulted my printed directions again. Veratrum was said to be specific against the rice-water discharges and cold sweats, which still continued. I dissolved a few pellets of veratrum and ordered a teaspoonful every ten or fifteen minutes, unless the patient was asleep.

Before I left the boat, however, an Allopathic qualm came over me, sharp as a stitch in the side, and I left orders that if the man got any worse, the pills must be given every half hour till relieved, and I might have added—or dead.

I retired to my couch, but not to sleep; like Macbeth, I had murdered sleep — at least for one night. The spirit of Allopathy, terrible as a nightmare, came down fiercely upon me, and would not let me rest. What right had I to dose that poor fellow with Hahnemann’s medicinal moonshine, when his own faith, no doubt, was pinned to calomel and opium, and all the orthodox pills, potions, poultices and porridges! I had not told him that I was going to practice Homoeopathy on him. His apparent relief was probably only a deceitful calm. Perhaps he was at that moment sinking beyond all hope, owing to my guilty trifling with human life. He was a drowning man, calling for help, and I had reached him only a straw! I was overwhelmed with strange and miserable apprehensions. I longed for the morning like a sick man, for I was sick in conscience and at heart.

I left my bed of thorns at daybreak and hurried to the boat, trembling with fear lest I should find the subject of my rash experiment cold and dead. He was in a sweet sleep. The sweating and diarrhoea had disappeared, and a returning warmth had diffused itself over his skin. He was out of danger and he made the most rapid convalescence that I had ever witnessed after cholera. I was delighted, a burden had been lifted from my heart —a cloud from my mind. I began to believe in Homoeopathy. I felt like some old Jew who had witnessed the contest between Goliath and David. How amazed he must have been when the great giant, who could not be frightened by swords or bludgeons or brazen trumpets, fell before the shepherd boy, armed only with a little pebble from the brook!

I remembered my case of croup, which Doctor Bianchini had cured so quickly, and I felt like giving the new treatment a little more credit for the cure. Let not my reader imagine, however, that I went enthusiastically into the study and practice of Homoeopathy, as I ought to have done. No, indeed !—it was two long years of doubting and blundering before I was willing to own myself a Homeopathist. We may be startled into admissions by brilliant evidence like the above, but we really divest ourselves very slowly of life-long prejudices and errors. I have cured many a man with infinitesimals, and found him as skeptical as ever. I myself witnessed the triumph of these preparations in scores—yes, hundreds of cases, before my mind advanced a step beyond its standing-point—“There is something in Homoeopathy, and it deserves investigation.”

My father, like the sensible man he was, did not sneer or scoff at my Homoeopathic experiments. He recognized the partial truth of the principle—“Similia similibus.” He used to say that he had too frequently cured vomiting with small doses of ipecac, and bilious diarrhoea with fractional doses of calomel, to question the fact, that a drug in minute quantities might relieve the very symptom which it produced in large ones. He came in one day from a bad (really hopeless) case of cholera, and proposed I should try my cuprum and veratrum on it. The poor fellow died, and quite a damper was thrown on my young enthusiasm. We expect everything—perfection, magic, miracle—from a new system. Allopathy may fail whenever it pleases—it has acquired the privilege by frequent exercise of it, but let Homoeopathy fail, and all inquiry ceases, until something forces it on our attention again.

When I visited Cincinnati, soon after, I had interviews with Mr. Barrett, and also with Doctor N. C. Burnham, the first Homoeopathic physician I ever conversed with, and obtained much surprising information about the Homoeopathic treatment of cholera and other diseases. I supplied myself with books and medicines, and began the systematic study of the system. I confess I found it very difficult and even repulsive, with the limited material at our command at that time. I discovered, however, what many Allopathic explorers fail to discern, that Homoeopathy offers us the only medical theory which professes to be supported by fixed natural law, and that it requires thorough scientific training to understand it properly, or to prosecute it successfully. I wonder now at the slow reception—the lazy, frequently interrupted study — the apathy, the indifference of that period. I would sometimes practice Allopathically for weeks together, and only think of Homoeopathy in obscure, difficult, obstinate, or incurable cases.

Singular injustice is perpetrated against Homoeopathy every day by both physicians and people. The Allopathic incurables—the epileptics, the paralytics, the consumptives, the old gouty and rheumatic, and asthmatic and scrofulous, and dropsical and dyspeptic patients — come to the Homoeopathic doctor for prompt, brilliant and perfect cures. Failing to obtain these after a few days’ or a few’ weeks’ trial, they go away and disseminate a distrust of the value of Homoeopathic medication. All these cases are treated better in the new than the old way. They are more frequently cured — much more frequently relieved. They live longer, with less pain and more comfort. But these are not fair test cases of the power of Homoeopathy. When Allopathy cleans its Augean hospitals of all such opprobia it will be time for us to show equal omnipotence. If a man wishes really to discover what Homoeopathy can accomplish, let him try it in acute, sharply defined, uncomplicated diseases, such as cholera, croup, erysipelas, pneumonia, dysentery, haemorrhages, neuralgia, and the various forms of inflammation and fever. Having settled its value in these simpler and better understood diseases, he can advance to its trial in the more complex, and he will never be so much disappointed as to be willing to relapse into the old cobweb theories and practices of the past.

The dysentery followed the cholera throughout the western country. I treated many cases Homoeopathically, and with admirable results. I had occasion to try my new practice on myself in this painful disease. I persisted in the use of my infinitesimals, although I suffered severely, and my father, becoming impatient, brought me a delicious dose of calomel and opium, which he requested me to take. I declined doing so, on the ground that I ought to be as willing to experiment upon myself as upon others. I made a rapid recovery. I had not then become as zealous a believer as a distinguished legal friend of mine in Mississippi, who vowed that he expected and intended to live and to die under Homoeopathy — to make an easy death and a decent corpse. I could not boast, either to myself or others, of the special superiority of Homoeopathy over the old system in dysentery, because my father’s Allopathic practice was quite as successful as mine. He gave very little medicine, and dieted very strictly. I insisted, however, and I believe correctly, that the average duration and severity of the disease were less under the new than under the old system.

In 1850 I moved to Cincinnati, and entered on a wider and more stimulating field of thought and action. My professional activities were sharpened and brightened; and yet, strange to say, my interest in Homoeopathy waned and almost expired. I had the books and medicines in my office, and occasionally prescribed according to the “similia similibus” but my studies, my associates, my ambition, and my general practice were Allopathic. I kept aloof from Homoeopathic physicians. I professed to believe that Homoeopathy had some indefinable value, but had received too imperfect and obscure development as yet to be trusted at the bedside. I wrote my first medical essay for an Allopathic journal. When I reflect on this course of mine, I am not surprised that a family sometimes uses Homoeopathy for a while, seems very much pleased with it, having every reason to be so, and then quietly glides back, under the influence of personal friendships or fashion, into the old, respectable, well-regulated dominions of calomel and Dover’s powder.

Every man has a magnetic or spiritual sphere emanating from him, which tends to bring others into rapport with him, and so impose his opinions and views upon them. A society or institution, whether a church, a political party, or a scientific school, is a large sphere, the aggregation of the individual ones, which has a powerful magnetic quality, binding all the similar parts in strict cohesion, and repelling from it everything dissimilar which would resist its bonds or question its authority.

The majority of men are unthinking, and they are drawn and held, like little particles of iron about a magnetic centre, unconscious of their slavery, and fondly believing themselves capable of independent thought and action. The medical profession—a vast, learned, influential and “intensely respectable” body, insensibly exhales from itself a sphere of dignity, authority and power well calculated to reduce its subordinates to a respectful submission.

This was the secret of my vacillation of opinion. My hopes, my aspirations, my friendships, my social position, were all associated with the old medical profession. I was again, as at Philadelphia, in the charmed atmosphere of colleges and journals, and hospitals and dispensaries, and medical authors and genial professors. I loved the books of the Old School; I admired its teachers, respected their learning, and coveted their good opinion. To array myself against what I so much honored and respected—to cut loose from these fashionable and comfortable moorings—to throw myself into the arms of those whom I had been absurdly taught to consider as less respectable, less scientific, less professional than myself and friends, was a task difficult to accomplish. The discovery and the acceptance of truth are alike painful. It is a continual warfare with one’s self and the world: it is a fight in which defeat is moral death, and in which victory brings no ovation. My inglorious repose under the shadow of the Allopathic temple was suddenly broken by the iron hand of a better destiny.

In the spring of 1851 I visited an uncle in the extreme South. I glided along on the swelling bosom of the great Mississippi, whose throb was communicated through countless tributaries to an area of European dimensions. I enjoyed the sunny air, the delicious perfumes, and the boundless luxuriance of that rich climate, which blends the charms and beauties of the temperate zone with those of the tropics. I threaded the dingy mazes of the Red river far upward toward its source, and hunted wolves and wild cats in the forests of Texas. I burst the thrall of books and parties and schools, and in the vast solitudes of nature I inspired a new air, a new spirit, a new liberty.

I was returning to Cincinnati, refreshed and invigorated by my excursion, when the cholera broke out among the German immigrants, who crowded the lower deck of the steamboat on which I had taken passage. The clerk of the boat, a personal friend, came to me and told me that I was the only physician on board, and requested my assistance for these poor people. I was surveying the medical stores in the large brass-bound mahogany chest which our river boats always keep, when the clerk remarked to me, “Ah, doctor, I have got a better medicine chest than that, from which I select remedies for such passengers as have good sense enough to prefer Homoeopathy to Allopathy.” With that he brought out a nice little Homoeopathic box, and I determined at once to make a grand Homoeopathic experiment on our Teutonic travelers. I committed the same ethical impropriety which saved the life of my flat boatman, but I made the fact, that I had no confidence in Allopathy for cholera, and the wishes of the officers of the boat, my excuse.

We put every new case on tincture of camphor, one drop every five minutes—enjoining absolute rest and strict diet. The fully formed cases were treated with cuprum, veratrum and arsenic, according to the symptoms. Many cases of cholera were immediately arrested. Thirteen passed into fully developed cholera, of which two were collapsed. There was not a single death. This outburst may have been of milder type than usual, for similar epidemics have occurred on plantations, many cases with inconsiderable mortality. I did not think of that or know it at the time, and my success made a powerful impression on my mind in favor of Homoeopathy. Two Old-School physicians came on board at Memphis, and were all suavity, examining my cases with great interest, until they learned that I was practicing Homoeopathy on them, when they turned up their noses and withdrew to a distance quite as agreeable to me as to themselves.

The discovery of the planet Le Verrier, by the great French astronomer, is often adduced as one of the most splendid triumphs of human genius. No eye had ever seen the distant globe. Le Verrier conceived the idea that a certain perturbation in the movements of the planets could be accounted for only on the supposition of the existence of another planet, of certain dimensions, occupying a certain orbit, at a certain distance beyond all the others. Powerful instruments were brought to bear on the sidereal spaces, and the new orb, first discovered by the mind, was revealed to the eye. The only fact in history which matches it in grandeur, and excels it in utility, is the prediction by Hahnemann, that camphor, cuprum and veratrum would be found the best remedies for cholera. No European physician had ever seen the Asiatic plague. No experiments had been made — no theories tested. Hahnemann, without ever seeing a case or prescribing for a patient, being guided by the eternal therapeutic law, which he had discovered, “Similia similibus curantur,” predicts the successful treatment as confidently as he would have directed the proper course of a vessel by the help of the magnetic needle.

I returned to the study of Homoeopathy with redoubled zeal. I not only read Hahnemann, but everything I could get hold of bearing on the subject, for and against. I can especially recommend to the beginner the back numbers of the British Journal of Homoeopathy, a splendid monument of Homoeopathic learning and talent, still flourishing, in its twenty-fifth volume.

I also proved medicines on myself— aconite, nux vomica, digitalis, platina, podophyllin, bromine, natrum muriaticum, and eryngium aquaticum, and became convinced experimentally of the truth of those Homoeopathic teachings about the action of drugs, which are revolutionizing the Materia Medica.

I sought the acquaintance of Homoeopathic physicians, and found Doctors Pulte, Ehrmann, Price, Parks, Gatchell, Bigler, and others, intelligent and cultivated gentlemen—the equals, morally, intellectually and socially, of their bigoted and ill-informed traducers. I began also to practice Homoeopathically with more precision and success than before. Indeed, I was bursting my chrysalis shell, and getting ready to soar into the golden auras of a better philosophy.

The last case I treated out and out Allopathically was that of a dear friend, a promising young lawyer. He charged me especially not to try my little pills on him, for my use of Homoeopathy was getting to be pretty generally known. So I treated his case, typhoid fever, with as much Allopathic skill as I could display. He became worse and worse. I called in the distinguished Doctor Daniel Drake in consultation, and Professor John Bell, of Philadelphia, then filling a chair in the Ohio Medical College, was added to the list of medical advisers. My poor friend lived six or seven weeks—his constitution struggling, like a gallant ship in a storm, not only against his disease, but against the remedies devised by his well-meaning doctors for his restoration.

Modesty of course demanded that a young man like myself should stand silent and acquiescent in the presence of such shining lights of the medical profession. But the spirit of free criticism had been awakened in my brain, and I watched the ever-varying prescriptions they made, and the shadowy theories upon which they were based, with mingled feelings of surprise, incredulity and pity. I mean no disrespect to these eminent and excellent gentlemen, both of whom treated me with the most genial civility, and paid me social visits after my formal separation from the Old-School profession. But having seen Allopathy practiced in a long and painful case, in the best manner and spirit, by its best representatives, I determined to abjure it, as a system, forever.

This determination was arrived at by the contrast between the two systems, which I was now enabled to make by my previous study and practice of Homoeopathy.

A few years earlier I would have received the dicta of Doctors Drake and Bell as words of oracular wisdom—I would have taken notes of the principles and practice involved in the case, and would have thought I had gained some invaluable knowledge from these consultations. What jargon to me was all their learned phrases about correcting secretions, equalizing the circulation, allaying irritation, obviating congestion, determining to the cuticle, etc., and all their various means and measures for doing these things, when I knew that bryonia and rhus, in very small doses, prevented the development of the typhoid condition, for the very simple reason that they produced it in large ones — every drug having opposite poles of action, one represented by large doses, and the other by small!

How useless, and even injurious, were their opium and hyoscyamus and lupulin, etc., checking secretion, benumbing sensibility, obscuring the case, when a few pellets of coffea would have produced sleep or quieted irritability! And then, how much better infinitesimal arsenic or mercurius would have checked that obstinate diarrhoea than all the chalk mixtures and astringents in the Materia Medica! And so of every feature in the case.

The fact is, there are many exceedingly valuable empirical preparations in Allopathy, for this, that, and the other morbid state or symptoms, but the general mode of philosophizing is false, vicious and irrational, and the resulting practice frequently destructive. Therefore, although I might continue to give quinine for intermittents, bismuth for gastralgia, etc., still, as I discarded all the Allopathic theories, and nine-tenths of their practice, having a better system, thoroughly practical, safe, prompt, pleasant and efficacious, I could no longer call myself, or consent to be called, an Allopathic physician.

Now arose a delicate and difficult question. If you believe that Homoeopathy is merely a reform in the highest sphere of medical science—that all scientific culture is preliminary necessary, and adjuvant to it, if you intend retaining many of the best Old-School empirical prescriptions, because your new system, although magnificent as far as it goes is still imperfect, —why do you cut yourself off from your old friends and associates, and assist in founding a new and antagonistic School of Medicine, instead of infusing the spirit of your reform into the old one?

Ah! but could I have done this noble work? Could I have taught the power of infinitesimals, and have reported my Homoeopathic cures in the established journals of medicine? Of course not. That failing, could I have written books on Homoeopathy, contributed articles to Homoeopathic journals, consulted with Homoeopathic physicians, and have remained in good standing and loving fellowship with the intolerant members of the Medico-Chirurgical Society? Of course not. My dignity, self-respect, candor, honesty, and spirit of independence, all demanded that I should send in my resignation to that Society, as to a party of gentlemen to whom my opinions and practice had become obnoxious.

I have now been a Homoeopath for fifteen years. I have practiced it in all our Southern diseases for thirteen years. Having studied both sincerely, I can contrast the two systems correctly.

In all acute diseases, from the worst of them, cholera and yellow fever, to the earache or a cold in the head, Homoeopathy cures more frequently, promptly and perfectly.

In the chronic and organic diseases it sometimes achieves brilliant results. But in some obscure, complicated or incurable cases, we have still occasionally to borrow the empirical crutches of Allopathy, for which we are sincerely grateful.

Imagine what our world would be like if allopathy (they don’t like that name) determined to communicate with homeopathy and work together. How much suffering would be relieved?

These are important statements about acute versus chronic. A long standing ailment (chronic) will require work with a homeopath to see if it can be remedied in full. Chronic took the person a long time to get to that stage, it would take time to reverse, relive and hopefully maybe cure.

Having been true to myself and my conscience, and, as I firmly believe, to science and humanity, I have so long ignored the scoffs, the taunts, the base insinuations of some of my old confreres, that I have almost forgotten they ever existed. Homoeopathy enjoys a steady, beautiful, perpetual growth, although the London Lancet still vomits its falsehood and slander. Homeopathy is not becoming more Allopathic, as some suppose, because the new converts who are crowding our School retain more or less of their old opinions and practice The genuine Hahnemannian spirit—the spirit similia in theory and infinitesimals in practice-was never more vital or progressive. It is the hope of our medical future—the guiding star of investigation—the pivot of truth.

Unfortunately organised allopathic organisers got the upper hand. But now is the time to reinvigorate this knowledge, as more awaken to the falsehoods of the Orthodox medical SYSTEM.

As to our professional assailants — the Simpsons, the Hookers and Holmeses of the day, and those who echo their oft-refuted statements, as they understand Homoeopathy about as well as the prosy old Dane did the character of Hamlet—we toss them the line of the poet—

“And you, oh, Polonius, you vex me but slightly “

Support Jack’s Work

If you find the content at Totality of Evidence useful for yourself or to help awaken your family and friends, please consider becoming a paid subscriber so I can continue to add to this historical record.

From time to time I’ll add a stack here, but most of my work is done on the website, your support here, supports my work there!

Otherwise share the website on social media and subscribe to my substack so you get my next stack in your inbox!

Thanks Jack. Wonderful post! Enlightening indeed!

Excellent post, thank you.